A Cry for Help

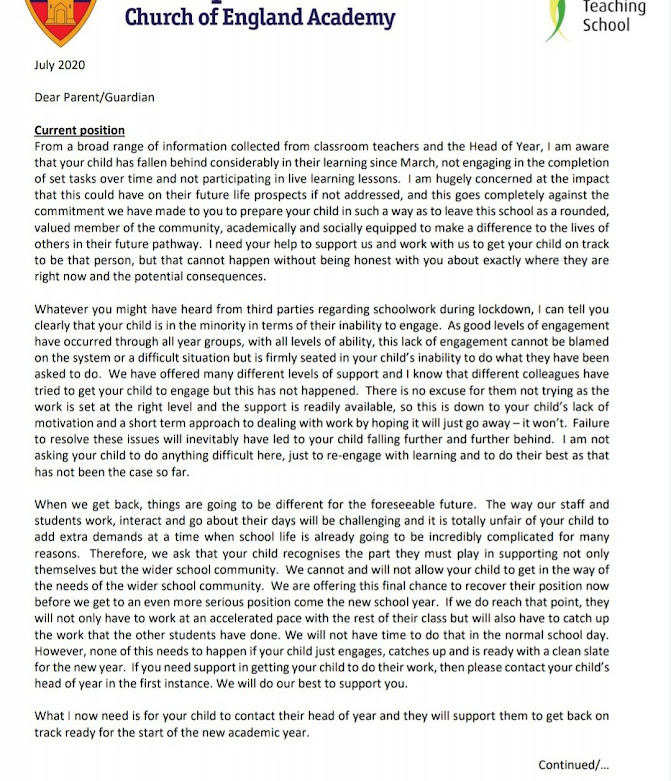

This letter's been doing the rounds on EduTwitter these last few days, sparking off all manner of heated debates and reaching the ears of the local press. An academy in Lancashire sent a rather angry missive to the parents of a student with autism who had apparently not been working hard enough during lockdown. It's worth reading, if you haven't already done so.

What's the first thing that strikes you? Is it the weirdly long-winded rambling? The poorly constructed clauses of the first paragraph? The way it's not personalised (it's evidently been sent to several parents), and yet at the same time still manages to come across as a deeply personal attack on the poor kid?

Or is this just an inevitable result of what's been happening in education these last 10 years or so? Because this has been coming. Iterations of this letter get sent out every term. It's unusual in its brutal honesty, perhaps. Like they've forgotten that they're supposed to hide their assault on the child's character behind a thin veil of euphemism. They've definitely let the mask slip to some extent, and they've exposed behind it the naked and undignified race for grades that has characterised this particular era of education reform.

I found myself reading it again and again. There was something else, something about the phraseology that kept haunting me, like a ghostly lament echoing down the walls of the empty school corridor. "I need your help"... "it is totally unfair of your child to add extra demands"... "school life is already going to be incredibly complicated"... "we will not have time". And I began to realise, this is desperation, not condemnation. This letter is not so much a rebuke of a child as it is a cry for help.

This head doesn’t need to be publicly shamed. It sounds like he needs a hug. Or at least a cup of tea and a good cry somewhere (at least) 2m away from me. He’s got problems. And as the child’s father put it, between shifts working at the local hospital, “they are simply passing their problems onto parents.” He’s right, of course. This head has allowed his own insecurities to drip from his pores onto his MAT-issued Chromebook and frankly it’s made a big mess.

But herein lies the crux of the matter. These school insecurities were built into the whole process of mass academisation ten years ago. And the people who led us to this point knew exactly what they were doing.

The academies sales pitch was designed to be attractive to large swathes of middle England. Bringing in some of the efficiencies and dynamism normally associated with the private sector so as to drive through a modernisation of creaking public sector institutions. It’s seductive, and at first glance seems relatively benign. Until. Until you start to see values shift towards those that serve the interests of the multi-academy trust, rather than those of the community. Until resources are diverted towards boosting outcomes that are easily quantifiable, and away from those outcomes that aren’t. Until you realise the creeping way in which, eventually, the relationship between the school and the child changes. And you find that schools have stopped asking what they can do for the child, and have started asking instead what the child can do for the school. Until you end up with letters like this one.

I was reminded of an excellent LRB article I read a few years ago by on the marketisation of British education. Stefan Collini was writing principally about higher education reforms, but the parallels with the move towards academies and free schools in the primary and secondary sectors, led by successive education ministers over the last decade or so, are striking.

The intentional 'destabilisation' of schools was seen as a positive driver of reform by the Tories. But only because they were unconcerned by the long term effects of this insecurity, which we are seeing today. A passionate belief in the power of market forces led them to assume that as long as there was competition between schools they would be compelled to improve. And they knew that for the competition to be genuine, school leaders had to know that the sword of Damoclese hanging above their heads was real.

And so the conservative strategy revealed itself. Make schools independent from government control, encouraging a range of new providers to enter the market. Introduce high-stakes competition, and the threat of sanctions for schools that fail to meet certain numerical targets (say, 30% A*-C). Schools will be under greater pressure to meet these targets, so grades will go up. And any that are struggling, don't need to be supported or protected because they are, all together now, independent from government control. Perfect.

Not quite. This threat of failing to meet numerical targets might be helpful when it comes to driving motivation in the world of business, or competitive sports. But when your job also involves looking after the wellbeing of vulnerable children (and parents) in your community, children with multiple ACEs, children exposed to domestic violence, children with SEN, it really isn't. Because you've got two targets that are at odds with each other. To ensure that average grade scores across the cohort keep going up year on year, and to look after the interests of vulnerable families and children in the community who will probably bring those grades down. The children who, to quote this letter, 'get in the way'. I know that leaders genuinely don't want to exclude kids. They don't want to write letters like these. But I also know that holding both of these seemingly conflicting, high-stakes goals in mind, day in day out, year after year, takes its toll.

By 2017 the number of heads who reported suffering from stress was up to 74%. By 2018 it was 80%. Last year it was up to 84%. Thank god 2020 has been so straightforward otherwise we might be looking at even higher figures again this year. And let’s not forget that this stress radiates all the way down the corridors. Leaders pass their stressors directly down to the people beneath them, who then do the same, until you are left with a sleep-deprived class teacher shouting at the children to get higher grades. And then you have leaders who are less able to contain the stress of those beneath them who might come to them needing help. One of the first things you learn in trauma informed practice is that unless you are in a reasonably good place, mentally, you’re not much use to those who aren't.

How can we expect to deal with the mental health crisis facing our children if we cannot deal with the one that's facing our staff? I'm trying to teach teachers how to respond to children who are overwhelmed, anxious, depressed, stressed, while dealing with the fact that these teachers themselves are experiencing all of these feelings and more. Hounded by the constant threat of performance related pay progression, constantly having to push kids in ways that they never envisaged when they first decided to go into teaching.

There is a long-term psychological impact of the disconnection between the intrinsic values you hold as an educator, and the quite different set of targets you are required to hit. Collini puts it better: “The logic of punitive quantification is to reduce all activity to a common managerial metric. This is part of the explanation for the pervasive sense of malaise, stress and disenchantment… It is the alienation from oneself that is experienced by those who are forced to describe their activities in misleading terms.” I didn't go into teaching wanting to increase the average progress 8 score of my class. I can't imagine many did.

What's the first thing that strikes you? Is it the weirdly long-winded rambling? The poorly constructed clauses of the first paragraph? The way it's not personalised (it's evidently been sent to several parents), and yet at the same time still manages to come across as a deeply personal attack on the poor kid?

Or is this just an inevitable result of what's been happening in education these last 10 years or so? Because this has been coming. Iterations of this letter get sent out every term. It's unusual in its brutal honesty, perhaps. Like they've forgotten that they're supposed to hide their assault on the child's character behind a thin veil of euphemism. They've definitely let the mask slip to some extent, and they've exposed behind it the naked and undignified race for grades that has characterised this particular era of education reform.

I found myself reading it again and again. There was something else, something about the phraseology that kept haunting me, like a ghostly lament echoing down the walls of the empty school corridor. "I need your help"... "it is totally unfair of your child to add extra demands"... "school life is already going to be incredibly complicated"... "we will not have time". And I began to realise, this is desperation, not condemnation. This letter is not so much a rebuke of a child as it is a cry for help.

|

| 12.12.2015 by Stephane Villafane |

This head doesn’t need to be publicly shamed. It sounds like he needs a hug. Or at least a cup of tea and a good cry somewhere (at least) 2m away from me. He’s got problems. And as the child’s father put it, between shifts working at the local hospital, “they are simply passing their problems onto parents.” He’s right, of course. This head has allowed his own insecurities to drip from his pores onto his MAT-issued Chromebook and frankly it’s made a big mess.

But herein lies the crux of the matter. These school insecurities were built into the whole process of mass academisation ten years ago. And the people who led us to this point knew exactly what they were doing.

‘The biggest lesson I have learned is that the most powerful driver of reform is to let new providers into the system.’ (David Willetts, 2011)

The academies sales pitch was designed to be attractive to large swathes of middle England. Bringing in some of the efficiencies and dynamism normally associated with the private sector so as to drive through a modernisation of creaking public sector institutions. It’s seductive, and at first glance seems relatively benign. Until. Until you start to see values shift towards those that serve the interests of the multi-academy trust, rather than those of the community. Until resources are diverted towards boosting outcomes that are easily quantifiable, and away from those outcomes that aren’t. Until you realise the creeping way in which, eventually, the relationship between the school and the child changes. And you find that schools have stopped asking what they can do for the child, and have started asking instead what the child can do for the school. Until you end up with letters like this one.

|

| Turbulence 21 by Melisa Taylor Metzger |

I was reminded of an excellent LRB article I read a few years ago by on the marketisation of British education. Stefan Collini was writing principally about higher education reforms, but the parallels with the move towards academies and free schools in the primary and secondary sectors, led by successive education ministers over the last decade or so, are striking.

“Deliberate steps have been taken to ‘destabilise’ the majority of institutions ‘prior to the entrance and expansion of the alternative providers”. (S. Collini, 2013)

The intentional 'destabilisation' of schools was seen as a positive driver of reform by the Tories. But only because they were unconcerned by the long term effects of this insecurity, which we are seeing today. A passionate belief in the power of market forces led them to assume that as long as there was competition between schools they would be compelled to improve. And they knew that for the competition to be genuine, school leaders had to know that the sword of Damoclese hanging above their heads was real.

"It is not Government’s role to underwrite independent providers that have become unviable." (Govt response to consultation on education reforms, 2012)

“We will continue to require that every failing school should become a sponsored academy” (DfE white paper, Educational Excellence Everywhere [sic], 2016)

And so the conservative strategy revealed itself. Make schools independent from government control, encouraging a range of new providers to enter the market. Introduce high-stakes competition, and the threat of sanctions for schools that fail to meet certain numerical targets (say, 30% A*-C). Schools will be under greater pressure to meet these targets, so grades will go up. And any that are struggling, don't need to be supported or protected because they are, all together now, independent from government control. Perfect.

Not quite. This threat of failing to meet numerical targets might be helpful when it comes to driving motivation in the world of business, or competitive sports. But when your job also involves looking after the wellbeing of vulnerable children (and parents) in your community, children with multiple ACEs, children exposed to domestic violence, children with SEN, it really isn't. Because you've got two targets that are at odds with each other. To ensure that average grade scores across the cohort keep going up year on year, and to look after the interests of vulnerable families and children in the community who will probably bring those grades down. The children who, to quote this letter, 'get in the way'. I know that leaders genuinely don't want to exclude kids. They don't want to write letters like these. But I also know that holding both of these seemingly conflicting, high-stakes goals in mind, day in day out, year after year, takes its toll.

| ||

|

How can we expect to deal with the mental health crisis facing our children if we cannot deal with the one that's facing our staff? I'm trying to teach teachers how to respond to children who are overwhelmed, anxious, depressed, stressed, while dealing with the fact that these teachers themselves are experiencing all of these feelings and more. Hounded by the constant threat of performance related pay progression, constantly having to push kids in ways that they never envisaged when they first decided to go into teaching.

There is a long-term psychological impact of the disconnection between the intrinsic values you hold as an educator, and the quite different set of targets you are required to hit. Collini puts it better: “The logic of punitive quantification is to reduce all activity to a common managerial metric. This is part of the explanation for the pervasive sense of malaise, stress and disenchantment… It is the alienation from oneself that is experienced by those who are forced to describe their activities in misleading terms.” I didn't go into teaching wanting to increase the average progress 8 score of my class. I can't imagine many did.

So staff morale has continued to decline, retention beyond three or four years is getting harder and harder. We can fight for higher pay, but ultimately there’s only so far you can go to compensate for a system that has teacher stress built into its design.

Behaviour is the communication of an unmet need. The behaviour exhibited by the Head who wrote this letter is telling us something. At some point we’re going to need to start listening.

Behaviour is the communication of an unmet need. The behaviour exhibited by the Head who wrote this letter is telling us something. At some point we’re going to need to start listening.

Comments

Post a Comment