An Unconditional Offer (Part 2) : Permanent Exclusion

Last September our 3yr old son came home from his pre-school with his ‘home learning journal’. 30 pages, each offering some sort of task with space for us to record what he has done at home to achieve it. Fun, enriching activities... play barefoot in the sand, make a den, climb a tree, all that kind of stuff. By Christmas I was naively wondering if we would have time to complete all these home learning tasks. Turned out not to be a problem. Two months into lockdown and I was spending 30mins with him on the High Road trying to get a shot of him "catching a raindrop" on his tongue. Anyway, one of the tasks stood out from the rest.

Other activities, nominally at least, required the child to actively do something to complete the task. Make a mud pie, grow a vegetable, whatever. But I found the task of 'experiencing unconditional love' confusing, being entirely reliant on factors outside of the child's control. What would happen to the child who was unable to complete this task? Is his fate to be punished twice, once by his family, then by his school? It's a preposterous thought. But it's not a million miles away from what's going on.

In my (secondary) school we don't set tasks like 'experience unconditional love'. What we normally do however is set tasks whose successful completion depends not just on cognitive or academic ability, but also on intra-personal skills that tend only to develop fully within an environment of unconditional love. Resilience, emotional regulation, risk-taking, self-belief. If they are unable to complete the tasks they are set, they will seek out other ways of feeling good about themselves. Patterns of behaviour develop, expectations are set. It is terrifyingly easy for a pupil to start heading down a spiral that can lead to permanent exclusion. I see kids on this slide every day, and we’re pretty good at predicting how it’s going to end for them. What we’re not so good at seeing, is how it all started. With a task they were never able to complete, through circumstances beyond their control.

All the children I've seen permanently excluded, have already to some extent excluded themselves. Excluding children permanently from school is merely a way of colluding with them in their own self-sabotage. It is a way of confirming to the child the image they already hold of themselves. It is an abdication of our duty as a key part of that child’s community, to do whatever it takes to get him off that downward slide, rather than send him hurtling down it at ever greater speed.

Because once a child has been excluded, and they are sent to the bottom of this spiral, very few ever manage to climb back up again. 4.5% go on to get a good pass in English and Maths. Over a third end up NEET, many of those end up in the criminal justice system. And of course correlation does not imply causation. There could be, and probably are, shared root causes hidden away in the distal, tangled web of early childhood traumas that account for both their poor life chances and school exclusion. But that’s the point isn’t it. If some form of early trauma is shaping the direction of their lives, then surely school exclusion is one of the only adverse childhood experiences that we as a society are in control of. In other words, if they feel rejected by adults who have come in and out of their lives up to this point, do we really want to be adding our name to that list?

I’ve already written about the carceral logic that underpins many internal exclusions, but permanent external exclusions are a horribly difficult topic to discuss in schools. I have read and seen enough to lead me to believe now that excluding someone permanently is morally wrong. But try telling a teacher or headteacher, dealing with a student that has been physically or emotionally abusive to their peers and teachers, that he cannot be excluded. Try telling the parents of the victims of this abuse. All these people are understandably and justifiably appalled and repelled by the notion that we cannot permanently exclude these children. Children who have been charged with bringing dangerous weapons into school. Selling drugs. Rape.

Those who have suffered feel no immediate need to care about what happens to these children once they have committed these offences. Their immediate craving, understandably, is for retribution. A public acknowledgement in no uncertain terms that this behaviour is not allowed, that it cannot be allowed. For if we cannot make such a statement, then where does that leave us? Where does that path go?

But we need to ask ourselves what we really want, not as victims of this child’s abuse, but as members of the society in which we live, in which the perpetrator lives, and will continue to live even if and when he is excluded. Why do we crave retribution? What good will it serve? Ultimately, do we just want him to be out of sight, out of mind? Because dealing with the underlying conditions that lead to the offence, or series of offences, is incomparably harder than just getting rid of him?

What about the other kids in the class? This is the hardest FAQ when you raise this issue with teachers. Surely they have the right to an education that isn’t ruined by one or two individuals that can’t behave? True. But what message does it really send to the other children when we do exclude? That it's ok to sacrifice a small number of children for the sake of the majority? That we deal with people with difficulties by pushing them away rather than understanding their needs and how to help them? I think this is the lesson that has been learned, historically, from decades of school exclusions, and I don’t think our society is better off for it. Is it good to teach them that the support offered by the school community is not unconditional? That if you cross a line this support will be removed? I guess I’m arguing here that you will never achieve genuine inclusion if it is conditional on factors outside of a child’s control. No-one can say they are truly inclusive if in the next breath they are selecting which children they are going to include, and which they aren’t. And in the long run we all reap the benefits of living in a society that is inclusive, and we all suffer from living in one which isn't.

When I talk to teachers about inclusion there are easy conversations and there are difficult ones. Many of these conversations trigger deep rooted emotional responses. When you say you want to create an autism friendly space for a mild-mannered child in their class it triggers all our inner feelings of warmth and compassion, helping a vulnerable member of our community to overcome barriers they had no part in erecting. It makes us feel big, important. The benevolent benefactor issuing charitable support to those ‘deserving’ souls who need our help. The practicalities might be challenging to say the least, but it's not hard to get them on board.

I am proud to work for one of the eight schools taking part in the Evening Standard's £1.5m campaign, launched earlier this year, to fund schools who are searching for alternatives to exclusion. But before attempting to change school policies, it is necessary first to change hearts and minds. I've picked out four principles that teachers will need to hold in mind for them to sympathise with the move to abolish exclusions:

Firstly, that these children are also victims of circumstance first and foremost, trying to overcome barriers that were not put up by them. Remove the language of victim and perpetrator. There are only victims.

Secondly, that subsequent behaviours are their way of communicating unmet needs rooted in environmental difficulties. They are not due to some innate characteristic. They are not ‘other’ to us, or ‘monsters’. Avoid the temptation to other them, to demonise.

Thirdly, that helping them is not demeaning to us as ‘authority’ figures. It is not undermining us. It is an active choice we are making, whereby we still have the power in this situation. We are still in control. We are actively choosing to include, rather than weakened by our inability to exclude.

Finally, we need to grow to understand that there is no ‘somewhere else’. People who are most keen to exclude are also the people who are keen to put up borders and fences, to separate society into ‘us’ and ‘them’. Who are most keen to ‘other’ those that transgress the hegemonic rules and norms of mainstream society. We need to remind ourselves that when we exclude someone, they are still there. Their problems are still there. Just because they are no longer in our school doesn’t mean they are no longer part of our world. That we are all connected by a common humanity should be a source of inspiration, not something to be afraid of.

Many children have not experienced unconditional love. Through their eyes, the world might look quite a different place. Genuine, trauma-informed inclusion has to be unconditional. This is a foundational principle of both inclusion and trauma-informed practice. Every time we permanently exclude a child, we drill another giant hole in these foundations, and we critically undermine the very structures that might stand a chance of helping them. Abolishing exclusion is probably one of the hardest pathways to inclusion there is, but it could also be one of the most important.

|

| Home learning task no.8 |

Other activities, nominally at least, required the child to actively do something to complete the task. Make a mud pie, grow a vegetable, whatever. But I found the task of 'experiencing unconditional love' confusing, being entirely reliant on factors outside of the child's control. What would happen to the child who was unable to complete this task? Is his fate to be punished twice, once by his family, then by his school? It's a preposterous thought. But it's not a million miles away from what's going on.

In my (secondary) school we don't set tasks like 'experience unconditional love'. What we normally do however is set tasks whose successful completion depends not just on cognitive or academic ability, but also on intra-personal skills that tend only to develop fully within an environment of unconditional love. Resilience, emotional regulation, risk-taking, self-belief. If they are unable to complete the tasks they are set, they will seek out other ways of feeling good about themselves. Patterns of behaviour develop, expectations are set. It is terrifyingly easy for a pupil to start heading down a spiral that can lead to permanent exclusion. I see kids on this slide every day, and we’re pretty good at predicting how it’s going to end for them. What we’re not so good at seeing, is how it all started. With a task they were never able to complete, through circumstances beyond their control.

All the children I've seen permanently excluded, have already to some extent excluded themselves. Excluding children permanently from school is merely a way of colluding with them in their own self-sabotage. It is a way of confirming to the child the image they already hold of themselves. It is an abdication of our duty as a key part of that child’s community, to do whatever it takes to get him off that downward slide, rather than send him hurtling down it at ever greater speed.

Because once a child has been excluded, and they are sent to the bottom of this spiral, very few ever manage to climb back up again. 4.5% go on to get a good pass in English and Maths. Over a third end up NEET, many of those end up in the criminal justice system. And of course correlation does not imply causation. There could be, and probably are, shared root causes hidden away in the distal, tangled web of early childhood traumas that account for both their poor life chances and school exclusion. But that’s the point isn’t it. If some form of early trauma is shaping the direction of their lives, then surely school exclusion is one of the only adverse childhood experiences that we as a society are in control of. In other words, if they feel rejected by adults who have come in and out of their lives up to this point, do we really want to be adding our name to that list?

|

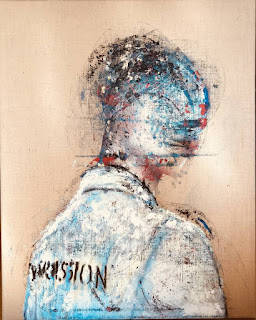

| Intermission by Ben Moebius |

Those who have suffered feel no immediate need to care about what happens to these children once they have committed these offences. Their immediate craving, understandably, is for retribution. A public acknowledgement in no uncertain terms that this behaviour is not allowed, that it cannot be allowed. For if we cannot make such a statement, then where does that leave us? Where does that path go?

But we need to ask ourselves what we really want, not as victims of this child’s abuse, but as members of the society in which we live, in which the perpetrator lives, and will continue to live even if and when he is excluded. Why do we crave retribution? What good will it serve? Ultimately, do we just want him to be out of sight, out of mind? Because dealing with the underlying conditions that lead to the offence, or series of offences, is incomparably harder than just getting rid of him?

"Exclusion conveys, to the other members of the class, that some young people are expendable" (Frequently Asked Questions on Abolition and School Exclusions)

What about the other kids in the class? This is the hardest FAQ when you raise this issue with teachers. Surely they have the right to an education that isn’t ruined by one or two individuals that can’t behave? True. But what message does it really send to the other children when we do exclude? That it's ok to sacrifice a small number of children for the sake of the majority? That we deal with people with difficulties by pushing them away rather than understanding their needs and how to help them? I think this is the lesson that has been learned, historically, from decades of school exclusions, and I don’t think our society is better off for it. Is it good to teach them that the support offered by the school community is not unconditional? That if you cross a line this support will be removed? I guess I’m arguing here that you will never achieve genuine inclusion if it is conditional on factors outside of a child’s control. No-one can say they are truly inclusive if in the next breath they are selecting which children they are going to include, and which they aren’t. And in the long run we all reap the benefits of living in a society that is inclusive, and we all suffer from living in one which isn't.

‘What about the other 29’ is one of the FAQs cited by the impressive grassroots activist group NME (No More Exclusions). They were keeping this on the agenda when others weren't, while at the same time reminding us of the greater challenges seemingly faced by black children in an environment where school exclusion is a constant risk. Black children are three times more likely to be excluded than white children. Schools, full of well-intentioned liberals, have perhaps become complacent on the matter of race in recent years. If we are now starting to belatedly appreciate that black people suffer from an unconscious bias and a systemic racism that runs through this country's authoritarian institutions, then we are deluding ourselves if we fail to acknowledge that schools are part of that very same system. But this is a long discussion, perhaps for another post.

|

| Missing IX by Juliet Malinowska |

When I talk to teachers about inclusion there are easy conversations and there are difficult ones. Many of these conversations trigger deep rooted emotional responses. When you say you want to create an autism friendly space for a mild-mannered child in their class it triggers all our inner feelings of warmth and compassion, helping a vulnerable member of our community to overcome barriers they had no part in erecting. It makes us feel big, important. The benevolent benefactor issuing charitable support to those ‘deserving’ souls who need our help. The practicalities might be challenging to say the least, but it's not hard to get them on board.

Talking about abusive children is very different. Talking about allowing them back in the classroom when they have abused a teacher triggers the opposite emotional response. Makes them feel small. Like the supposed hierarchy has been flipped. Weak, belittled. Not in control. Which makes sense, once you've learned that abused children need others to feel what they themselves have been feeling.

Children who have experienced trauma will often invite the rejection they feel they deserve. That is the real failure of an exclusive society, to make someone feel like they are never going to be included, but that they are not worthy of being included. So they exclude themselves to save themselves from the pain and shame of having others do it to them. Again. When we exclude we not only reinforce the self-image they already hold, we also cut off the means by which people might help them to develop others. When a child presents us with a self-portrait that is damaged or hurting, we should help them draw a new one, not laminate it, give it back to them and send them on their way.

Children who have experienced trauma will often invite the rejection they feel they deserve. That is the real failure of an exclusive society, to make someone feel like they are never going to be included, but that they are not worthy of being included. So they exclude themselves to save themselves from the pain and shame of having others do it to them. Again. When we exclude we not only reinforce the self-image they already hold, we also cut off the means by which people might help them to develop others. When a child presents us with a self-portrait that is damaged or hurting, we should help them draw a new one, not laminate it, give it back to them and send them on their way.

|

| Form Without a Form by Yulia Luchkina |

I am proud to work for one of the eight schools taking part in the Evening Standard's £1.5m campaign, launched earlier this year, to fund schools who are searching for alternatives to exclusion. But before attempting to change school policies, it is necessary first to change hearts and minds. I've picked out four principles that teachers will need to hold in mind for them to sympathise with the move to abolish exclusions:

Firstly, that these children are also victims of circumstance first and foremost, trying to overcome barriers that were not put up by them. Remove the language of victim and perpetrator. There are only victims.

Secondly, that subsequent behaviours are their way of communicating unmet needs rooted in environmental difficulties. They are not due to some innate characteristic. They are not ‘other’ to us, or ‘monsters’. Avoid the temptation to other them, to demonise.

Thirdly, that helping them is not demeaning to us as ‘authority’ figures. It is not undermining us. It is an active choice we are making, whereby we still have the power in this situation. We are still in control. We are actively choosing to include, rather than weakened by our inability to exclude.

Finally, we need to grow to understand that there is no ‘somewhere else’. People who are most keen to exclude are also the people who are keen to put up borders and fences, to separate society into ‘us’ and ‘them’. Who are most keen to ‘other’ those that transgress the hegemonic rules and norms of mainstream society. We need to remind ourselves that when we exclude someone, they are still there. Their problems are still there. Just because they are no longer in our school doesn’t mean they are no longer part of our world. That we are all connected by a common humanity should be a source of inspiration, not something to be afraid of.

Many children have not experienced unconditional love. Through their eyes, the world might look quite a different place. Genuine, trauma-informed inclusion has to be unconditional. This is a foundational principle of both inclusion and trauma-informed practice. Every time we permanently exclude a child, we drill another giant hole in these foundations, and we critically undermine the very structures that might stand a chance of helping them. Abolishing exclusion is probably one of the hardest pathways to inclusion there is, but it could also be one of the most important.

|

A wonderful, human and honest article. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThat's really appreciated, thank you.

DeleteChildren who are already hurting will then hurt themselves and/or others. They feel bad about themselves, other people and the world they are in. We need to promote positive feelings in schools to start to reverse the downward spiral. Teachers need help to do this - especially to understand the roots and implications of trauma and not to take challenging behaviour personally. I used to teach hard to manage pupils and have written several books on practical strategies that help kids stay included and also support teacher wellbeing. See www.growinggreatschoolsworldwide.com

ReplyDelete